It’s an image that perfectly captures the emotion and devastation of a recent natural disaster. A small girl in a boat wearing an orange life vest, clutching a puppy. The image, purporting to show a survivor of Hurricane Helene, was seen by millions on social media and around the web.

The problem? The image is completely fake. Not even a photo out of context from a different hurricane. It’s a fabrication spun up by generative AI.

As the technology advances, improving day by day, fake images will only improve, leaving people wondering how to discern reality from fabrication.

Dan Petty, a trainer with the Radio Television Digital News Association, recently came to Albuquerque to offer insight and training to local journalists on how to best detect and debunk mis- and disinformation.

With the general election only days away, Petty has concerns about how AI may be used to spread false information about candidates, voting and election procedures.

“Today is the day the worst AI and generative AI models are going to be in your lifetime,” said Petty, whos day job is director of audience strategy for ProPublica. “It will be better tomorrow, and better the day after that and the day after that. Which is not necessarily better for humanity.”

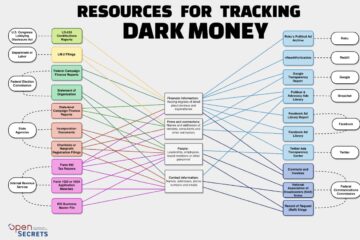

This year, RTDNA partnered with Google News Initiative to bring training on digital tools for election coverage to newsrooms. Petty presented several tools focused on mis- and disinformation, fact-checking and source verification.

Many resources can be found on the News Initiative website, he said.

Misleading images often fall into two categories – whole-cloth AI generated and contextual, Petty said.

An example he showed of an image used out of context showed helicopters circling the frozen blades of a wind turbine. It was circulated in 2021 after freezing temperatures disabled the Texas power grid, to support the false conjecture that the power system failed because turbines froze.

The picture was actually from 2018 and was taken in Sweden, where wind turbines do freeze and need to be de-iced.

A Google image search is a good way to check the context of a photo, and help determine when and where it was originally posted, if it comes from a news outlet and more.

If you’re using Google Chrome as your browser, right-clicking on an image lets you search photos and images using Google Lens. There are other reverse image search tools such as RevEye and TinEye, Petty said, which will produce similar results.

Google Fact Check pulls together results from a variety of fact checking websites which can be searched in one central location. The tool also offers a reverse image search fact check, which you can request beta access to under the FAQs and the question, “Why don’t I see the image context tab?”

There are also a host of tools for journalists at journaliststudio.google.com, including Google Fact Check.

Other Google tools include Pinpoint, which allows journalists to upload a large collection of documents and analyze them using Google search and AI technology.

Google also offers Notebook LM, a tool that can create eerily realistic audio conversations based on uploaded files, among other features. Journalists can apply for advanced tools.

The Chrome store offers a browser extension, InVid & WeVerify, which can be used for a variety of fact checking. There’s also deepware.ai, that can scan a suspicious video to look for synthetic manipulation.

If you want to test your skills at detecting AI images, check out whichfaceisreal.com, which is part of a website put together by two professors at the University of Washington in Seattle – Carl Bergtrom and Jevin West – authors of “Calling Bullshit: The Art of Skepticism in a Data-Driven World.”

Even with all the tools on the internet, Petty reminded reporters they still need to use some basic online sleuthing techniques – check to see if the information exists on other platforms. When was the profile created? Does the account have friends and family members as part of their audience? Is the profile picture real? (Reverse image search is your friend.)

Petty also recommended checking to see if the account is “verified,” but advised not to trust accounts verified on X.

“The barrier to entry is $8,” he noted.

Verifying if something is real takes time, he reminded the reporters at the training.

“You have to keep fact checking, putting the truth out there,” he said.